Welcome to PaulWertico.com!

The Sound of Two Hands Talking - Lessons with Paul Wertico

By Steve Anisman

Imagine that it's 1969 and you get the chance to spend some time with Ringo Starr. Not just the chance to say hello, but the chance to take a lesson, to share some wine over dinner, to listen to dozens of CDs and compare notes, and to hear advanced recordings of some of his upcoming projects. Not only that, but Ringo wants your opinion on things, and you end up friendly with him - he even calls you later just to say "hi."

I had the unbelievably good fortune to experience a parallel situation this year. Since I was in high school, my "Beatles" has been the Pat Metheny Group (PMG), and my "Ringo" has been Paul Wertico.

I first saw him perform in 1985 on the First Circle tour, and that concert completely changed the way I look at music, drums, and drumming. I had never seen anyone combine such intense musicality with raw power and an overwhelming technical mastery of the instrument as Paul did that night. Not only that, but the music itself was incredible. Overnight, I went from being a hard-core Neil Peart wannabe to being a jazz fan. It's taken me 13 years to begin to understand what Paul does behind the drumset - fortunately, I had the chance to have many of my questions answered directly.

Through months of badgering Paul and his management company via phone and e-mail, I was eventually able to wear him down to the point where he agreed to give me a lesson in Boston on one of his rare days off during a tour with the PMG. We didn't have access to a drumset, so we were able to spend the hour talking to one another and working on a practice pad.

The trademark Paul Wertico drum part is on the tune "The First Circle," and this song was the first thing we discussed during our lesson. I had heard Paul's playing on this tune described as "two-hand lead," meaning that each hand was playing a separate part on a separate ride cymbal. I wanted to understand how Paul approached a challenge like this. He described his approach as "letting my hands talk to each other." In much the same way that the different members of a jazz band each function independently, yet also respond to one another's playing and work as a single unit, Paul allows the rhythms generated by one hand's playing serve as the idea to which the other hand responds. The musical energy flows from one hand to another, as in a conversation.

In a conversation, sometimes one person is talking, sometimes the other is talking, sometimes both talk at the same time, and sometimes neither talks. In an overly simplified form, the drumming analogy can be expressed rudimentally. (In fact, Paul has used a rudimental approach to teach drumset coordination to many of his classically trained students. See Roy Burns' "One Surface Playing" for the classic example of this style of teaching.) In this framework, the interplay is expressed as "R"'s, "L"'s, rests, or flams (actually, "double stops", with both hands playing at the same time).

When you allow yourself to explore a style of playing in which the hands truly interact and respond to one another, rather than one hand leading and the other hand following, you open yourself up to a world of amazing possibilities. As I've tried to implement these ideas in my own playing, I've found it difficult to allow my hands to play on their own - I tend to fall back on patterns I've played for years. To avoid this tendency, I find that I need to really concentrate, and that listening to what I'm doing makes all the difference.

Paul has used this "two hands talking" approach in a fascinating way, one that has allowed him to create unique and challenging rhythms in support of the music he plays. Rather than playing separate ride cymbals with each hand, Paul has applied the concept to the more common posture of his right hand on a ride cymbal and his left hand on the snare. Again, neither hand "leads," as with traditional jazz drumset playing. Instead, both interact, interweaving with what the other is playing. By playing the left hand at a very low volume, however, Paul emphasizes the right hand's half of the "conversation."

Consider the analogy of Bach's Two-Part Inventions. As a whole, the compositions are beautiful. Each composition, however, is made up of two separate parts, with each hand's melody, harmony, and rhythm supporting those played by the other hand. At the same time, however, if you listen to either hand individually, it stands on its own as a compelling musical statement. The same can be said for the individual parts of the "two hands talking" method in drumming, as you can tell by listening to the unique ride "patterns" that Paul generates.

Like most drummers, I'm used to thinking of the right hand as leading the rest of my body, so letting this technique happen can be a difficult thing. It took a lot of practice and effort until I could relax to where I wasn't fighting the strange rhythms coming from my right hand, or insisting on filling in what felt like "wrong" empty spaces. When it happens, though, you feel it work and can't help but smile. This one insight alone has allowed me to really expand my vocabulary as a drummer.

This approach was only a small part of what we discussed during our lesson, however. We soon moved on to more technical aspects of drumming. We started with a discussion about posture. To Paul, staying relaxed is important, as a PMG show can go as long as three hours, nearly all with him in the driver's seat.

Paul stressed the importance of keeping correct posture with the shoulders down and relaxed while playing, not hunched up aggressively. He also places his cymbals within easy reach. The close proximity allows him to conserve energy by not having to move around the set or carry the full weight of his arms with his shoulders while playing ride patterns.

Paul explained that a good deal of his physical conditioning and posture training are courtesy of his wife Barbara. She is studying to become an instructor in a technique known as "Pilates" (Pih - lott' - eez), a form of strength and flexibility training that is usually used by dancers. Paul has been using some of the techniques, and has noticed increased strength in his lower back-he says that it "strengthens muscles you'd otherwise never pay attention to"-along with increased stamina and control while playing. The fact that his back is strong is evident when you watch him play, and it's something that he is quick to recommend. Explains Paul, "If your center is strong, everything else can be strong, too."

This awareness of his center of gravity is exceptional, and most noticeable when Paul erupts in a flurry of motion and sound while seemingly not moving his body at all. He can appear like a marionette at times during a set-his lower back is still, relaxed and straight, with all of the motion radiating out from that spot. He relaxes his elbows completely, which he says lets the energy flow (and surely his blood, too) through his arms with ease.

Even during rudimental passages, such as the interlude in the song "Minuano (Six-Eight)", his arms are totally loose and flowing, which allows the effortless movement of his sticks. Paul explains that this has helped him achieve a wide musical variety of sounds coming from the snare drum, with a wide range of tones and volumes.

The next technical area we covered was grip. Like many drummers, I was taught to play the drums and hi-hat with a palm-down grip, holding the stick between the pad of my thumb and the side of my forefinger - usually between the first and second joint, counting in from the fingertip. For the ride cymbal, I was taught to rotate my hand so that the grip stayed the same, but the thumb was on top. The motion I tried to produce was a consistent up-and-down line. This approach is certainly a good standard to learn, and it leads to consistent, dependable, and reproducible results. The mechanics are sound, and it has gotten me a long way in my drumming.

One of the requirements of playing with Pat Metheny, however, is that you be able to fully explore the range of expression of your instrument, and Paul fits right in with this attitude. In fact, Pat Metheny has discussed the things he looks for in a drummer (see the December '91 issue of Modern Drummer), and Paul fits the bill exactly.

For Paul, this expressiveness is a natural extension of his playing philosophy, and his unusual approach to his instrument. He is almost completely self-taught, and has forged a unique way of understanding drumming. He believes that a drummer's instrument isn't actually the drums themselves, but that instead, it is the drumstick. He has spent a lot of time perfecting his approach to drumstick (and, of course, drumset) playing, and it shows in his versatility.

It all starts with his grip. He usually plays with palm down, whether on the drums, hi-hat, or cymbals. He uses a variety of grips, depending on what the music requires. For songs that require each stroke to sound the same as the one before it, such as "How Insensitive" or "Are You Going With Me?", Paul will use a technique best described by Murray Spivak. He uses the side of his thumb (that part of the thumb that faces straight up when you lay your hand flat on a table) as his fulcrum, rather than the pad of that finger. To add consistency, he will support the stick with both the middle and ring fingers.

When a more variable approach is called for (such as in "The First Circle" or "Have You Heard"), Paul will rely more on the fulcrum created by pinching the stick between the pad of the thumb and the first finger, removing the supportive fingers from the stick entirely. This approach lets the stick float freely and reduces the tension in the hand. Holding the stick this loosely can allow the stick to "sing", or sustain, more. There are also a variety of other subtle ways that Paul will change his grip in order to achieve the wide variety of sounds he is called upon to produce.

By simply working on a practice pad, we were able to generate a series of pitches and varied timbres by changing the way we held the stick and moved it through the air. Spend a few minutes with a pad and a stick and see what you can get to happen. By choking down with the fulcrum fingers (thumb and forefinger), you can dampen the tone you produce. You can exaggerate this effect by letting the supportive fingers (middle and ring fingers) increase the amount of contact they have with the stick.

The angle of attack can also make a drastic difference. Paul teaches that the characteristic up and down motion many people are taught can have negative effects on their ability to express musical ideas effectively. Try playing a slow single stroke roll with the sticks moving straight up and down - this produces a characteristic sound. Next, try playing this same roll, probably slower, but let the sticks strike the pad (or drum, or cymbal) from off to one side or the other, not from straight above the pad. Try a variety of angles, and notice that the sound you produce is rounder and fuller than it had been when you played with an up-and-down motion, since the stick is moving with the sound being produced, not against it.

Changing the style of grip that you use also will affect the sound you generate. A "tympani style", or "French" grip - with the thumb on top and the palm parallel to the wall, will produce a tone completely different from a more traditional grip. Finally, you can completely relax your hold on the stick at the moment of impact, which will let the natural tone of both the stick and the drum (or cymbal) ring. I've known drummers who play quite loudly, and to avoid breaking sticks, they would almost throw the stick at the cymbal from an inch or two away, and catch it when it bounced. This, of course, will result in the greatest degree of sustain possible.

One of the challenges that Paul put to me during our lesson was to try to produce the same sound by using two different methods. He had me hit the pad with a normal, fairly loud stroke, then he asked me to make that same sound without lifting the stick more than an inch or two off the pad. In this case, all of the force has to come from the fingers and the wrist, and it's hard to do. When you feel like you've got it, use one hand and try to play a series of single strokes, alternating between the full stroke and the "compressed" stroke, increasing the speed as you go. Trying to keep the volume even as you do this makes for a great stick control exercise.

A final subtlety of controlling the instrument has to do with what is called "catching the bounce." If you've ever tried to play a double-stroke roll on a pillow, you're familiar with this technique. A double stroke roll on a hard surface is performed by letting each stick bounce once - you control the bounce by adding pressure subtly to the stick as it makes contact with the head, and the stick is then pushed back towards the head to make the second stroke of the double stroke. On a pillow, however, there is no natural bounce, so the fingertips and the wrists work in a more intricate way to produce the roll. The trick is to play the first stroke with the wrist, and the second stroke with the fingertips. As you try to produce a double stroke roll on a pillow, your hands will naturally make the correct compensations - it isn't as hard as it sounds, and it has dramatic benefits. Learning this technique will certainly increase your control over your instrument, which is a worthy goal for any musician. It will allow you to roll with brushes or mallets, and to more accurately control each note you play on any surface. In basic terms, learning this technique strengthens the relationship between your hands and your instrument - the sticks (or brushes).

With all of this technique available to Paul during a show, the next question I had was: "What do you think about when you're up there?" Paul said that other than obvious things such as solid time and groove, there are really only two things he thinks about when he's performing: sound and energy. He concentrates his energy on producing a rich collection of tones on the cymbals (and drums), making sure that they all blend well, one into the other. To achieve this blend with the PMG is a difficult feat, as the music often calls for the characteristic sound of flat ride cymbals. Paul recalled Jack DeJohnette's comment that Jack picks cymbals that sound like his drums, so he can present a cohesive sound. Paul noted that this is difficult in his situation, since flat rides don't really sound like any drums, having their own unique timbre. In order to bridge the tonal gap between these cymbals and his drums, Paul uses the snare drum, tuned fairly tightly, but with the snares loose enough to buzz. This snare functions as an intermediary between the other drums and the flat rides.

When it comes to playing the cymbals, he tries to make sure that the tips of his sticks are constantly moving from one region of a ride cymbal to another, to bring out all of the textures that cymbal has to offer. He tries to make sure that he's playing a range of dynamics within each phrase. The upper and lower ends of a range can rise for loud passages and fall for soft ones, but he tries to make sure that there always is a range of volumes, so the dynamics are never static.

Paul went on to say that his primary concern has to be for the "shape" of the song he's playing. Like most drummers, Paul has to provide the heartbeat for the band that he's in, and with musicians of the caliber in the Pat Metheny Group, you need to have a strong command of your instrument to be able to drive the band. Paul tries to provide support for the soloists, to infuse them with energy when they build to climaxes, and to bring the band back down when necessary. On top of all of this, the PMG relies heavily on pre-recorded material during their live performances. This means that Paul must also be locked in with the sequenced parts coming over his monitor.

Of course, Paul's skills are built on the foundation of his own musical influences. I was surprised by some of the music he had me listening to when we spent some time in a record store. He ended up buying discs by groups that had influenced him as a young drummer, such as King Crimson, the newly released BBC sessions of Led Zeppelin, a live Soft Machine album, and some discs by Nazz and Blue Cheer which were fuzztone (early metal) bands from the late 60's. Although this isn't his usual style of music, it does show an openness to music in its many forms, which is one of the hallmarks of Paul's playing. He plays a wide variety of different music well, because he has a wide variety of influences. Of course, these include Roy Haynes, Max Roach, Sid Catlett, Art Blakey, Buddy Rich, Gene Krupa - all the greats.

If you ever get the chance to take a lesson from Paul, by all means try to do it. He's a gifted teacher, who barely picked up a stick the entire time I was with him - he was interested in improving my playing, not in showing me his. As I've tried to put his ideas into practice, I've been impressed by both the immediate results I've seen in my playing, and by the challenges that I know I'll be struggling with for years to come. Paul's approach is deceptively simple - he teaches his students to extend their ideas of how drums can sound, and then gives them the tools to mold these added colors into complex and creative new musical forms.

As a result of my time with Paul, I've felt my playing loosen up considerably. I'm beginning to hear how the separate parts of my drumset can relate to one another as a musical whole. I'm finding that I'm less tired at the end of a practice session or a gig. Perhaps most importantly, I'm finding more subtleties to listen for in my playing, the playing of the other guys in the band, and in how they all can complement one another.

I've included some transcriptions so you can see some of what Paul is playing during some of his more memorable moments with the Pat Metheny Group.

TRANSCRIPTIONS:

Baião bass drum pattern on "Toms for Talia":

![]()

A recording in which you can hear Paul improvise and solo over this ostinato is on the song "Toms for Talia" (at 1:53) on his CD "The Paul Wertico Trio - Live in Warsaw!" Paul plays a baião pattern on his bass drum and all four quarter notes on his hi-hat as an ostinato, and he uses the "hands having conversations" approach with his hands. This is a useful ostinato to practice over - Paul says that in his case, he's now got it to the point where he doesn't even notice he's playing it anymore, and he can play just about anything he wants to over it.

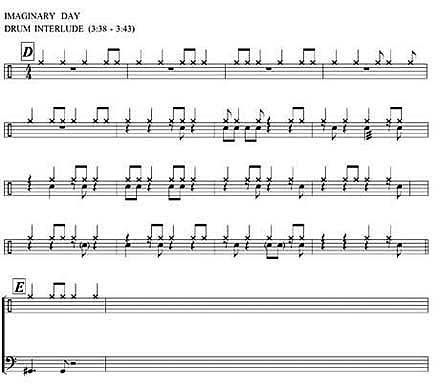

Ride cymbal & snare drum at 3:30 of "Imaginary Day":

This ride cymbal gets about 20 seconds of complete silence to itself, and Paul had to create a ride pattern with enough musicality to carry the song during this time. Listen to this and see if you think he's done it...

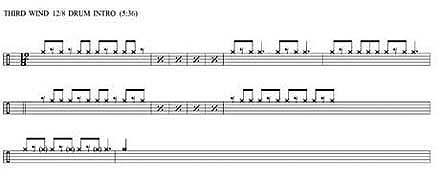

Ride cymbal & snare drum on the beginning of "Third Wind":

This is just a good example of a latin-flavored "hands talking" type of ride pattern that really pushes the music forward.

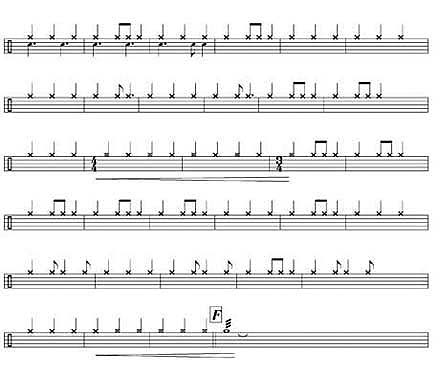

Ride cymbal on "Third Wind" after interlude (intro into 12/8 section):

This starts out as an "on the beat" pattern of (1-1-3-3), and Paul ends up inverting the rhythm, playing it backwards (3-3-1-1) and "off the beat" - the downbeats are rests, not played notes. It gives a driving, propelling feeling to the music, and it fits perfectly.

Ride cymbal & snare drum on "The Heat of the Day":

I think this is a great example of the incredible work that Paul has displayed in the past few years with the Pat Metheny Group. This must be heard to be believed...

For the original version of this article, visit Steve Anisman's web site.