Welcome to PaulWertico.com!

Chicago Jazz Magazine's January/February 2008 Feature Interview

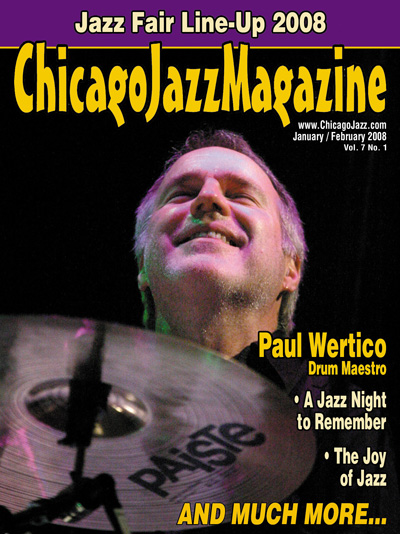

Paul Wertico - Drum Maestro

One of the most versatile and musical drummers in music today, Chicago's Paul Wertico became a member of the Pat Metheny Group in 1983. During that time he appeared on ten CD's and three videos with Pat, and has toured the world many times. Also during that time, he won seven Grammy Awards, numerous magazine polls, and received several gold records. Paul left the PMG in February of 2001. When he is not touring, Wertico divides his time between studio work, producing, session playing, and leading his own groups, and has played with such jazz greats as Eddie Harris, Lee Konitz, Dave Liebman, Sam Rivers, Bob Mintzer, Terry Gibbs, Buddy DeFranco, Roscoe Mitchell, Evan Parker, Jay McShann, Herbie Mann, Randy Brecker, Jerry Goodman, Ramsey Lewis and many others. He's currently a member of both the Larry Coryell Trio and the Jeff Berlin Trio. For seven years (2000-2007), he was also a member of the legendary Eastern European rock band, SBB. In 2004, Wertico was named one of the "Chicagoans of the Year" by the Chicago Tribune.

Wertico is also active in the educational field. In addition to teaching privately for almost forty years, he currently serves on the percussion faculty of Northwestern University and the jazz faculty of the Chicago College of Performing Arts at Roosevelt University, where is was appointed Interim Head of Jazz in 2007.He's written educational articles for magazines such as Modern Drummer, DRUM!, Drums & Drumming, and Drum Tracks, as well as for Musician.com. He also performs drum clinics and master classes at universities, high schools, and music stores in the U.S. and around the world, and has performed at the International Association of Jazz Educators' International Conferences. He has also released two instructional videos, Fine Tuning Your Performance and Paul Wertico's Drum Philosophy.

He's also released seven co-led recording projects: a self-titled LP, Earwax Control, and a live EWC CD entitled 2 LIVE; a self-titled LP, Spontaneous Composition; a drums/percussion duo CD (with Gregg Bendian), entitled BANG!; a double guitars/double drums three-CD set (with Derek Bailey, Pat Metheny, and Gregg Bendian), entitled The Sign Of 4; and two piano/bass/drums trio CDs (with Laurence Hobgood and Brian Torff), entitled Union and State Of The Union.

Wertico's debut CD as a leader, entitled The Yin And The Yout, received great critical acclaim including four stars in DownBeat magazine. His 1998 CD is a live recording of the Paul Wertico Trio and is entitled Live In Warsaw!. It received four-and-a-half stars in DownBeat, and features guitarist John Moulder and bassist Eric Hochberg. Each of Wertico's releases-Don't Be Scared Anymore (2000), StereoNucleosis (2004), Another Side (2006), and Ampersand (2007)-break new ground, and defy categorization, merging and destroying the traditional bounds of music, most notably jazz and rock.

Additionally Wertico played drums on Paul Winter's 1990 Grammy nominated release, Earth: Voices Of A Planet, and also played on and produced a number of CDs for various artists including vocalist Kurt Elling's Grammy nominated releases, Close Your Eyes (1995), The Messenger (1997), This Time It's Love (1998) and Man In The Air (2003). He also served three terms on the Board of Governors of the Chicago Chapter of NARAS (The National Academy of Recording Arts & Sciences).

Chicago Jazz Magazine: You're self-taught on drums?

Paul Wertico: Yes, I'm self-taught on the drum set. When I was twelve years old my family and I moved to Cary, Illinois, and my parents suggested that I take up a musical instrument-anything except the drums-but that's of course what I really wanted to play. So in sixth grade I joined the school band and that's where I learned how to read music and where I learned how to play the snare drum and the other instruments in the percussion section. I actually didn't get a drum set of my own until I was fourteen, after I graduated from the eighth grade, so I would go over to my friends' houses and play on their drum sets. It's funny, but I picked it up instantly-it just came naturally. After I got my own drum set, I remember once asking my mom if I could take some drum set lessons from a local drum instructor and she said something like, Oh, you don't want to be overly influenced by anybody, it's better to do your own thing. And that's exactly what I did. So, through buying tons of records and by going to see lots of people play live, and then asking them loads of questions, that's what pretty much got me going in the right direction. Luckily, for whatever reason, I also had good natural technique, coordination and speed, plus I've always had a great love of melody, so I always approached music with a sense of form and development, as opposed to just playing a beat. Those were definite advantages for an aspiring drummer.

Chicago Jazz Magazine: So what records were you buying?

Wertico: Now, we're talking the mid-1960s here, so obviously I was listening to a lot of great rock music. However, many of my first records were also jazz recordings. I remember going to a Goldblatt's department store one afternoon with my parents. The store was having a blowout sale on Atlantic LPs-some of the LPs were even in mono. But for literally a few pennies, I bought recordings like John Coltrane's Coltrane Jazz, Ornette Coleman's Ornette On Tenor and Charles Lloyd's Love-In-many things that were very new to me. That really got me into listening to modern jazz.

Chicago Jazz Magazine: Isn't that very unusual for that era? For most kids wasn't it the Beatles or the Stones?

Wertico: Yeah, I guess, but I really loved both rock and jazz equally, as well as loving various types of ethnic music from Africa, Chile, Tibet... I think one of the reasons my style has developed the way it has is because I really didn't differentiate or discriminate between the styles. If something sounded good and it spoke to me and moved me, then I would explore that music further. Through exposure to those records I learned the language of music and then I put all those different elements together into a big musical stew. At that time in Cary, I remember that there was a National Food Store that carried LPs near one of the checkout counters. That's where I bought Fresh Cream. I didn't even know who Cream was, but I bought their first LP based solely on the liner notes on the back of the record jacket. That's where I also bought The Mothers of Invention's first LP, Freak Out!, as well as the first LPs of Vanilla Fudge, Led Zeppelin and Jimi Hendrix. I also bought various jazz recordings there by artists I didn't know, just because they were visible and available, as well as classics like Buddy Rich Swingin' New Big Band. Nowadays, most stores don't carry much, if any, music, so kids don't have that same opportunity to pick up something just because it looks interesting. They might shop on Amazon.com or CD Universe, but that's not going to be the same experience as just impulse buying-buying something that seems cool or has a nice cover or an enticing paragraph about the band. Those were good days for creative music, regardless of genre, because new music was available everywhere.

Chicago Jazz Magazine: It reveals an adventurous spirit that you would take a chance on buying things that you hadn't heard of or were not familiar with. Is that something that describes you?

Wertico: Oh definitely. I'm an only child and I think I've always been pretty adventurous. I've bungee jumped, skydived, paraglided, parasailed, scuba dived and flown aerobatic planes, so I've always just gone and done whatever I felt that I wanted to do and tried to experience new things. Luckily, even at a young age my parents were very tolerant. But I never got into any trouble either because I was basically a good kid. As far as my early adventures in music, I was extremely fortunate to have two wonderful music teachers-an extremely good grade school band director named Vern Pahde, and a really great high school band director named Donald Ehrensperger. Both of these gentlemen were totally supportive and they both also let me "do my own thing," no matter how outrageous my ideas might have seemed. They never squashed my spirit and I'm still thankful to them to this day! I guess they saw that I had "something" and they helped nurture it.

Chicago Jazz Magazine: Your bio says you became a professional at age fifteen.

Wertico: Yes, that's true. I played some early gigs around the area with the first rock band I was in called The Rudeberry Blues Effect. We played songs by Cream, The Who, Led Zeppelin, Nazz and Blue Cheer. I was also in various musical ensembles at Cary-Grove High School, including their jazz band. By playing in those bands, other people heard me and started hiring me for real gigs. So all of a sudden here I was, age fifteen or sixteen, playing with professional players in the area. I remember playing a place in Elgin, IL on weekends-I won't name the club because I don't know if it's still there and I don't want to get anybody in trouble-where I'd sometimes play until 4:30 in the morning. It was fantastic!

Chicago Jazz Magazine: Did you end up going to college?

Wertico: Yes, I had a nice scholarship at Western Illinois University where I studied percussion with Gary Chaffee, who later became famous for his books on linear drumming. I remember he was quite young at the time, about twenty-five. I literally had it made at school-I had my own car, my own apartment, I was playing drums in the top jazz band and playing tympani in the symphonic wind ensemble, but then I quit school during the second quarter after I sat in with Cannonball Adderley's band. They were doing a rhythm section clinic at WIU one afternoon-Roy McCurdy was drumming, Walter Booker was playing bass and George Duke was playing piano. All the WIU drum students, as well as Gary, sat in at their clinic, but for some reason I didn't feel like doing it. Then during their last song my friend said, "Oh man, go play!" and I took the sticks out of Roy's hands mid-tune and finished the song and the place went nuts. I talked to Roy McCurdy afterwards and I said, "Man, I really want to play, I don't want to be in school." Now, I was a good student-I got all As and Bs, but at that point I really wanted to be out in the real world playing drums. Roy said to me, "Yeah, I think you should be out there playing." So, I quit school the next day. Then I moved back home for a while and eventually started gigging with various players in and around the area. After that, one thing kind of led to another.

Chicago Jazz Magazine: When you came to Chicago how did you survive? Obviously it takes some time to get gigs and so on.

Wertico: After I left school I went back to living at home in Cary with my mom-my father had died. I went to McHenry County College for about a year and started playing with different people in the Chicagoland area. Once that happened, I started making enough money that I was able to rent a house in Elgin. Rents were pretty cheap back then. But there were also some lean times. I remember this one Italian restaurant in Elgin had an all-you-can-eat pasta special on Tuesday nights, so I would basically not eat anything on Monday and just go nuts on Tuesdays. [laughs] When you're young and totally obsessed with music like that, sometimes you don't always think about reality as much as you should. You're basically driven by what you love, and I was no exception. I remember I used to get home from gigs at two or three in the morning and then I'd practice till dawn. At the time I was living by myself in a tiny corner house in Elgin. It was summertime and I would put on headphones and I'd start practicing, playing along with recordings of Frank Zappa or Jeff Beck or Miles Davis and so on. One time my neighbor next door came over one afternoon and said, "Hey, didn't you hear me beating on your door at 4:30 in the morning?" I said, "No!" He said, "You're lucky because I was going to kill you!" [laughs] I was so obsessed with music that nothing else seemed to even exist. I think a lot of really serious musicians are like that. It's their true passion. I often tell my students that too, especially the ones that are truly driven. That it's a gift, but you have to manage the gift. It's destiny in a way. But drummers don't always make the ideal neighbors! [laughs]

Chicago Jazz Magazine: Do you remember a defining moment when you said, "I've arrived"?

Wertico: No, never, because I still love to practice, I still love learning. Not to sound pretentious, but you never really "arrive", so it's important to always enjoy the process of getting there. Maybe that's one of the reasons that I like trains so much-people take planes and they're only interested in getting to their destination. If you take a train, even though it's significantly slower, it's the actual process during "getting" to your destination that makes the trip so enjoyable. It's the same thing with music-art is always a work in progress, so if you're truly an artist, you really can't ever be bored; there's always something to learn. So there's an inherent danger and an illusion when you win a Grammy or you play Carnegie Hall and you go, Wow, this is it--I've finally arrived!, because in reality, a week later you might be out there still scuffling for work. However, thinking you've "arrived" is different from getting to the actual point of where you know who you are, and can finally enjoy what you do and have confidence in knowing that what you do, you do well. That's more about understanding and accepting who you are as opposed to resting on your laurels. Also, once you achieve having a style and an identity, then anything you do in your life should help strengthen that style and identity. But you never "arrive"...you expand.

Chicago Jazz Magazine: One of the criticisms you hear of younger players today is that they don't have soul. Technically speaking they are great, but many seem to lack a feel for the music.

Wertico: I guess have to agree to some extent. I hate to say that, but I just went to Symphony Center the other night and there were some amazing young players performing, but it was really difficult to remember anything that they had played. They were very technically advanced, but it sounded like that's all they were concentrating on. As opposed to phonetic development, or even playing something that's sort of sloppy for the effect-showing some kind of emotion. The emotion-that's what always got to me, no matter who I was listening to. I might be listening to a blues drummer on a Howlin' Wolf record who probably couldn't even execute a "proper" rudiment, but that drummer, in their own way, would "get to me" just like Buddy Rich would "get to me." So the musicians that have a wide emotional range, as well as an intellectual range, I believe, are the ones that really can relate something to the audience and have the audience relate to them.

Chicago Jazz Magazine: Why do you suppose there's less emotional quotient today among young musicians?

Wertico: Well, I think it's a couple of things. With so many DVDs and so much information out there, a lot of young players learn without actually "being there." Take jazz for instance. So much innovative music started out with some poor kids playing, just trying to get off the street. So they expressed their life experiences through their instruments. Nowadays you have kids that just want to play, and they're taught mostly technique-and there are so many tools available to them-but they really don't have much to say with all that technique. However, and this is always a point of contention, I believe it's always important to keep an open mind when discussing topics like this because you also don't want to sound like some old stodgy guy saying, Well, you know, it was better back in the day. Things are just different now. Times change and so does music!

Chicago Jazz Magazine: Following that line of thought, do you think it's more likely that you're going to find emotionally gifted players from other countries, say, in a Latin American country or in Africa, where life for a young musician is tougher?

Wertico: Well, that's a great question. Everybody, whether they realize it or not, brings their life experiences with them. I've been to South America many times and there are some killer players down there, as well as in Europe and elsewhere-places like Poland, France, Norway, Italy, Israel-there are some amazing players out there. Yeah, it's a different thing. But I try never to say that something's "good" or "bad." It's just different, and we react to it differently according to our own experiences and sensibilities. But it was strange thing for me to go to that concert I mentioned earlier and hear such an amazing amount of technical facility and not be moved. It was like, Wow! So this proves that that's not the end all, after all. It's really the human element that has to translate somehow. And that's not to say that those players that I heard won't find that eventually, or maybe I'll grow and I'll listen to their music in a different way. Also, like I said earlier, music reflects the times. Now we are in the computer age and everything is fast; we are in the e-mail, Internet and cell phone age, so maybe that's what some current music is emulating. It may seem a little bit less human to those of us that have been around for a while and have experienced our own views of the world, but that doesn't necessarily make it less valid...it's just different.

Chicago Jazz Magazine: Other than allowing time to pass to another epoch is there a remedy to this?

Wertico: Well, that implies a negative-it implies there's a problem to be solved. Some of it can be our age too. The older you get the more you have seen and the less you are mystified by things.

Chicago Jazz Magazine: Well, let's say that you thought one of your students should consider playing with more emotion. How would you direct them to find that emotion?

Wertico: You know, it's funny, but most of my students do play with emotion. I'm not sure if it has anything to do with me relating the concept of playing "from the inside out" to my students, or playing them music that is very emotionally based, but most of my students do play from that gut level. It's a powerful thing-artists are supposed to make the listener reflect inside, so maybe some of the things that you and I don't like to hear, or can't appreciate yet, actually still is art, because it's making us look at ourselves and question our own values and belief system. We experience and filter other peoples' music through our own limitations, as much as it's created and expressed by the artists' limitations. It's pretty interesting.

Chicago Jazz Magazine: We don't want to belabor the subject, but...

Wertico: No, it's a great subject to talk about!

Chicago Jazz Magazine: One of the suggested cures for gaining "feel" is to sit in with the masters, with the people that are maybe in their seventies now. Players who in some cases use almost no technique and are virtually all feel, which will teach young players a different mindset toward the music.

Wertico: Well, there are less and less of those all the time. Unfortunately that's part of the deal, too. Even many of the people who are still alive now are actually second-generation musicians, including those who are in their seventies and eighties. The first-generation jazz musicians, the people that actually invented jazz, most, if not all of them, are dead. I went see one of my all time favorite drummers, Roy Haynes about a month ago, and he's in his mid-eighties. It was wonderful to see him play and still sound and look so vital. Unfortunately, another legendary drummer, the great Max Roach-who was one of Roy's peers-died recently. So Roy is one of the few guys left from that generation and like I said earlier, even he and Max are second-generation players. The musicians that discovered jazz are basically all gone. So there are a fewer and fewer older players still performing and in general there's not a lot of opportunity to play with some of those people. However, a lot of the older players actually like to play with younger players because it keeps them motivated too. For instance, Art Blakey always hired new musicians, younger musicians, because young musicians have that hunger...that drive, that fire and that young attitude and fearlessness. However, many young students aren't lucky enough to play with the masters. I think another part of the problem is that some students just play along with records and don't go out to hear great musicians play live often enough. Take Jamie Aebersold records, for instance-which, when used properly, can be quite beneficial. They're valuable teaching tools in many respects, but I've also seen too many student horn players think of a rhythm section as just being a background track for their solos. Whereas true jazz is about communication-it's all about playing together and having a musical conversation. It's not just you talking and everyone else is supposed to be subservient. Some of those new technologies foster that kind of attitude and I believe that is antithetical to the true spirit of jazz.

Chicago Jazz Magazine: Let's get back to your early years in Chicago.

Wertico: Well, I was in this outrageous experimental band called Earwax Control that I truly believe never received its due. I met those guys, Gordon James and Jeff Czech, back in '72 after I left college and moved to the suburbs. Before that, I started playing with a girl singer named Adrian Smith. She was signed to RCA records and we toured extensively around the Midwest. After that, I was in a band that included Steve LaSpina, the great bass player that plays with Jim Hall, and Randy Waldman, an incredible pianist who was living in Niles, Illinois at the time and who's gone on to play with Barbra Streisand, Frank Sinatra, Michael Jackson and many renowned artists, and Doug Sharf, the guy that plays trumpet and keyboards on the Svengoolie television show. One time Steve called me up to out to go to Elgin to jam with some guys I'd never heard of. So all of a sudden I'm playing with Randy and he's "eating up" the song "Bye-Bye Blackbird" at a breakneck tempo in every key with all this incredible technique, and in the background there's this other keyboard player named Gordon James, who's house we were jamming at. Now, Gordon didn't play with a lot of technique, but I really loved what he did. So after everybody else split, he and I hung out and we hit it off. Gordon started telling me about some bass player friend of his named Jeff Czech. The next day I went back to Gordon's house and played with him and Jeff and that's how Earwax Control was born. It was a perfect situation for me because it was a totally experimental band. At first we played Yusef Lateef tunes and Freddie Hubbard tunes, but soon we developed into a band that was completely freeform. Jeff was a wonderful player and eventually he started breaking onto the Chicago scene. So he would get a gig in Chicago and then he would get me on it. Then I'd get a gig in Chicago and I'd get him on it. Gordon did a little of that too, but Gordon was content to stay out in the northwest suburbs to play and teach. That was a great experience. At about the same time I met a musician named Ross Trout, who was a guitar player that had been Pat Metheny's roommate at University of Miami for a while. Through Ross I met bassist Steve Rodby. So all of a sudden things started morphing into these different groups of people that were all playing different types of music, all of which I loved. I think Jeff might have gotten me on the Bill Porter gig, as well as the Joe Daley gig. I mean, it all happened just like that. I never did a promo package or even had a business card-it was just word of mouth. But, Chicago had a much more solidified scene back then. For instance, the Lincoln Avenue scene had great clubs like Ratso's, Orphans, Collette's, Wise Fools Pub and the Jazz Bulls, so you could go up and down the street and you could go and sit in with people and hang out all night long. That's not happening anymore. Today, there are still some great clubs around of course, but there's no focused scene where people can just go from one place to another to listen, learn and play. The networking was totally organic-it wasn't like, Hey, baby, here's my card! [laughs]

Chicago Jazz Magazine: So obviously you had connections to Pat Metheny.

Wertico: That connection probably came through Ross Traut and/or Steve Rodby. I think it was about '77 that I first got a call from Pat Metheny. He had already put out two recordings of his own by that time-the second one, Watercolors, had just come out-and he wanted me to do some gigs with him. For some reason, his drummer couldn't make a few gigs, so he asked me to do them, but I turned him down because I was going to be playing at the Jazz Showcase during that same time with Joe Daley, Muhal Richard Abrams and Steve LaSpina. I had been playing with Joe for a couple of years by then and this was going to be a big gig for us and I really didn't want to let Joe down. I think that Pat was impressed with the fact that I was loyal to Joe. In this business, if you can stay with a band for years and have the same friends for years, that's usually an indication that you're somewhat stable. So I think Pat appreciated that. A few years later, I joined a band called the Simon & Bard Group. In '82, we were playing a club in Portland, Oregon. Steve Rodby and Pat came into the club to hear us after their concert and a few weeks later I ended up getting the Pat Metheny Group gig. It was just one of those things. So that's how it happened. In January of 1983, I did my first European tour with the PMG, and that gig lasted until I left in 2001. I did ten recordings and several videos with Pat over those eighteen years.

Chicago Jazz Magazine: Were you allowed to do other projects while playing with Pat Metheny?

Wertico: Sure, I've always done more than one project at any one time. It's important to always keep things moving. I like so many different types of music, so it's great when you do other things. Then when you come back to your regular gig, you have all kinds of new ideas and techniques. You never want to just sit there and vegetate. The whole thing about being a musician is growing, exploring and refining.

Chicago Jazz Magazine: When you joined Pat in '83 you were joining an existing band?

Wertico: I'm not sure exactly what happened with Danny Gottlieb and the PMG, and frankly it's no one's business. Danny is a good friend of mine and he's a wonderful musician. I don't know what happened with them. Who cares? It doesn't matter because it worked out fine for all concerned. But when Pat called me to play, he actually called me to play drums for a percussionist's audition, so I flew out to Boston-I believe it was the day before Christmas Eve. It's funny, but I actually wasn't that familiar with the PMG's music when I flew out-I mean, I didn't really listen that much to Pat's music to be honest with you. Of course I liked and appreciated what I'd heard of it, but I was into things that had a bit more of a harder edge. Anyway, we played for about a half an hour for the percussionist's audition and after the percussionist left, Pat, Steve, Lyle Mays and myself ended up playing for about another twelve hours! I remember that one of the songs we played was one of the group's better known compositions entitled, "Are You Going With Me?," which, frankly, I had not heard before. Pat then told me to learn some of the music and he flew to Chicago a week later, and he, Steve and I played once again. A few days later Pat called up and asked me if I had a passport. I said, "No." He said, "Get one!" A few weeks later I was touring Europe as a member of the PMG! However, I never went out to Boston to try to cop a gig-I just went out there to play some music with some great musicians.

Chicago Jazz Magazine: In joining an existing ensemble what was expected of you, to learn the tunes as they had been performed?

Wertico: That's a good question. Actually, no. Of course, there were certain things in the drum parts that were part of the arrangements, but Pat was looking for something different. When I got the gig it was unbelievable. There was so much music to learn and so little time to learn it before we headed off to Europe. Steve was a huge help. The first gig I played with Pat was in Oslo, Norway. I had never been to Europe before, let alone Norway. I brought over the drum set I normally used on local Chicago gigs and it instantly fell apart. [laughs] So I'm playing the second tune and my snare drum strainer fell off and I had to duct tape it on for the rest of the three hour and forty-five minute show. That was trial by fire. There were also so many musical details to learn. And Pat's music has a very well thought-out concept. I mean, it's not just about blowing tunes-there's a lot of depth to the concept. On those first tours-you'd crack one musical nut and there would be ten more nuts to crack, and so on and so on. It was very intense, but I learned a lot musically. I also immediately set out to get some equipment endorsements! [laughs]

Chicago Jazz Magazine: Why do you suppose that the Pat Metheny Group was so popular at that time?

Wertico: Well, part of it was the times-Pat's even said that it would be much harder to do that nowadays. Part of it was it was just that era-you know, the mid-seventies, early-eighties. That wonderful venue, Amazing Grace, in Evanston, was in full swing, bringing in fresh diverse talent from all over the world. FM radio was playing so many new artists and changing the radio format from the three-minute-single AM radio format, and there was a lot of growth and positivity. Pat's music was also relatable for both musicians and lay-people-it's interesting because it's complex music, but at the same time it's melodic-the melodies were such that you could whistle them in the shower. Also, although it was thought of as jazz, but it also had rock elements and Brazilian elements and things like that. The combination of different styles that made up that music was quite unique at the time.

Chicago Jazz Magazine: Not to take away from the music, because the music is wonderful, but didn't Metheny have a good marketing machine behind him?

Wertico: Oh sure. Pat's agent, who was also his manager, Ted Kurland, was one of the heavy hitters, and I think still is. He's Kurt Elling's agent too. But they had strong marketing power back then. So that helps too-you know, it's not just about the music, unfortunately. Kids sometimes think that if they practice enough, that it's naturally going to "happen." In an ideal world, maybe that would be true, but this is still a tough business, and if you can have some people in your corner that have some clout and have some connections and can move your music ahead of other people standing in line, that's the way it is. Miles, the Beatles, everybody had that.

Chicago Jazz Magazine: There aren't too many jazz musicians in Chicago that can boast seven Grammy's. Where do you keep them?

Wertico: Oh, I just have them around. I mean, it's funny-they're all dusty. Seriously, if I showed them to you right now they are just sitting over the fireplace; one's on a stereo speaker. [laughs] I mean, in one respect, it's the greatest. The first time I won a Grammy I remember the PMG was rehearsing in Coventry, England for an upcoming European tour and my wife (who was then my girlfriend at the time) called me up and said, "Wow, you just won a Grammy!" It was unbelievable because you never really think you are actually going to win a Grammy. And I must admit that having seven of them is really something special. People say that's a major accomplishment and it is. But the real accomplishment was in making the music. I mean, the Grammy itself is a wonderful honor-it's a beautiful recognition. But, it's an award, and you have no control over that. Even though during the Grammy process they try to be fair, bands that are well known still have a better chance of getting a Grammy than somebody else that only a handful of people know, because it's still a voting process. Just like anything else, it's part of the real world. The Grammy people try to get a good balance of things, but it's impossible to know about every CD that's coming out every year.

Chicago Jazz Magazine: Walk us through the process of putting together a Pat Metheny album.

Wertico: Oh god, how long are we going to talk about Pat? I mean it's weird to keep talking about the past...

Chicago Jazz Magazine: It's a long and important part of your career.

Wertico: Absolutely, no doubt about it and I'm proud of my past accomplishments. Well, okay, to answer your question, each record was different. The first recording I did with the PMG, First Circle, was recorded and mixed in, I believe, five days. We basically just hammered it out and that was it. The later records would take up to six months. We would work on basic tracks for a week or so and then everything was layered on top. The basic rhythm tracks were done with sequencers or click to give a perfect bed on which to lay more tracks. But each recording had its own process, so it really depends on what recording we're talking about.

Chicago Jazz Magazine: Does he come in with charts and say, "I've got it all laid out"?

Wertico: No, no, he never did that. That's the thing-he really let us do what we wanted to do as long as it worked within his concept. I always tell my students, You should do what you want to do, but if you're in a band, it's the composer, the producer, the arranger, the leader and the artist that you have to make happy, if you want to work and serve the music first! But you should always strive to be yourself because you don't want to lose yourself, either. So Pat would have some lead sheets that he wrote out either on the Synclavier, or in later years on a computer, as well as a demo to listen to. Then we would just run through material. Sometimes we would practice it for a couple days and then take it on the road for a week or two, and then go into the studio. On the last recording I did with him, Imaginary Day, we rehearsed for only about a half a day and then we immediately went into the studio and started recording. On that CD, we didn't tour with the material at all before recording it. Also, sometimes during the recording process, sometimes we'd get a good take, but upon listening to the playback, we'd say, Oh man, that 3/4 bar should be a 5/4 bar! So then we'd record the whole song all over again, just perfecting the arrangement. Sometimes that was a major pain, but it usually turned out for the better.

Chicago Jazz Magazine: Not only have you won seven Grammy's, but you also spent some time with NARAS, the organization that presents the Grammy Awards.

Wertico: Right, I served three terms on the Chicago Board of Governors of NARAS.

Chicago Jazz Magazine: What prompted you to do that?

Wertico: There was a local Grammy party in Chicago one year when we were up for a Grammy and my wife and I went to it and some people at the party asked me if I was a member of NARAS. I said, Well, no. And they said, Well, you should be! So I joined, which is kind of unusual for me because I'm not much of a "joiner." [laughs] Later they asked me if I wanted to be on the Board of Governors and I said, Well, yeah, sure! It was fascinating-I met a lot of real interesting, dedicated people and I would probably do it again. They also support a lot of important music education programs that aren't that well known to the general public.

Chicago Jazz Magazine: Tell us about some of the programs that people aren't aware of.

Wertico: Well, there's MusiCares. MusiCares is a program that gives money to musicians in need-not just NARAS members, but people in the music business that have fallen on hard times or are in a serious health crises. If someone is really ill or they're destitute or need an operation, MusiCares will look at their case and they'll usually give them some money. And it's all done totally confidentially-they don't even announce who they gave it to. They also try to get music programs into the schools, trying to get people to know more about music. It's really interesting. It's not just about the glitz and glamour at all. NARAS is trying to advance the art of music and trying to get kids to learn more about music-they're actually trying to help people. It's so great that they are actually trying to do something. I'd always look at the different people on the Board of Governors and realize they're all first-rate professional people.

Chicago Jazz Magazine: Tell us about your relationship with your wife, Barbara. You have a musical relationship.

Wertico: Oh yeah, we go way back to when we met in '76. It was love at first sight and it still is after all these sightings! She was also in the Pat Metheny Secret Story Band, so we toured all around the world in 1993. She's written a lot of great songs as well. I've recorded some of her compositions on my CDs. She's also co-written numerous songs with Jim Peterik-from the bands Survivor and the Ides of March-and bassist Bill Syniar. Some of their compositions have been recorded by bands like Mecca, Khymera, and The Doobie Brothers. Barb's an extremely talented and beautiful musician.

Chicago Jazz Magazine: Does it make it easier or more difficult to be in a relationship where you share music at such a high level?

Wertico: All I can speak is for my own experience. It's been totally incredible. I've known her for over thirty-one years, so she totally knows the real me, and she understands what's really going on. Before she actually went on the road with me as a member of the Pat Metheny Secret Story Band, it was easy to suspect that every night was about partying and good times, but once she saw how much work it actually was and that I wasn't screwing around, it made going on the road a lot easier. [laughs] I think that solidified the fact that this is indeed a job. I mean it's a job that you love, but it's basically a profession and it can get pretty grueling sometimes. I like to say that we actually get paid to travel-we play for free. The fun part is going on stage and playing with great musicians and doing your thing and getting recognition for it. But the rest of it--being away from home, the travel, the hotels and sometimes the general working conditions--that's really what you get paid to deal with.

Chicago Jazz Magazine: We have to ask: You know Jim Peterik...

Wertico: Yeah...

Chicago Jazz Magazine: Your dog's name is Rocky; your daughter's name is Talia...

Wertico: Oh, that's interesting, I never thought of that.

Chicago Jazz Magazine: Any connection with the Rocky movie?

Wertico: No, not at all. Rocky was named Rocky when we got him. And the name Talia-my wife came up with that. I know there's Talia Shire, but it had nothing to do with the Rocky movie. Even so, I have to admit that that is a little coincidental and kind of hilarious.

Chicago Jazz Magazine: Having played with musicians from all over the world, do you think there's a "Chicago" sound?

Wertico: Chicago musicians have a tendency to really master a lot of different styles, in order for them to work. I think that's why a lot of Chicago musicians do so well after they move to different cities. Chicago is a work city. It's a blue-collar city-let's face it. So, in order to survive, musicians from here end up taking a lot of different types of gigs. But it's not like it used to be when I was getting on the scene. Many of those diverse opportunities for musicians to work and to experience new things have unfortunately either greatly diminished or have vanished completely. Also-and I'm only talking about jazz now-with the exception of a few musical movements that affected the entire world, such as the Austin High Gang and the AACM, Chicago doesn't always get its due. A lot of times when people think of Chicago-they think of it as a city that likes its swing. Sometimes it's somewhat conservative in its swinging approach as well. Many players here like to play down the middle of the beat. Now, when you think of New York drummers-and there are always exceptions, of course-but in general, New York players tend to play ahead of the beat. It's a more aggressive and urgent approach. I've always felt that I played more like a New York player. In fact, Larry Gray, the great Chicago bass player, told me that after he played with drummer Bob Moses, he better understood where I was coming from. Certain cities definitely have their own sound. When I think of New Orleans for instance, I think of their sound. Also, depending on the era and the type of music, many cities have had their own sound-Detroit, Memphis, Kansas City, Philadelphia, San Francisco, Oakland and Seattle come to mind. There are even some stylistic differences between the South Side and the North Side of Chicago. I love it all! Some of the freer South Side players like Fred Anderson, The Art Ensemble of Chicago-all those guys are totally great. I've also always loved playing experimental and avant-garde music. I was in a band called Spontaneous Composition with Rich Corpolongo and Doug Lofstrom in the eighties that played 100 percent improvised music, hence the name. I love free music. But all Chicago music is real. And if you think of some of the jazz musicians that come from Chicago-from Gene Krupa to Jack DeJohnette, from Bud Freeman to Von Freeman-way too many to name here-there are so many truly great players that have come out of this city. Not to mention, that Chicago also has tons of great blues. It's one of the world's blues capitals. Not to mention great rock bands, house music, gospel... So man, when you tell someone that you're from Chicago, you can't help but be proud!

Chicago Jazz Magazine: You've chosen to stay in Chicago all these years even you've had other options. Why did you choose to stay?

Wertico: Well, I think when you're young, you fantasize about moving to New York City or Los Angeles or someplace like that. But my wife still has family here. Plus, after playing in the PMG, it doesn't really matter where I live so much anymore because I can fly out and do gigs anywhere. And I honestly love it here-I love the city and the people. New York is great-there's so much going on there, but I think that it's harder to live and raise a family there. Here, we are in the middle of the country, the people are friendly and it's a very beautiful, livable city.

Chicago Jazz Magazine: Who does their work well on the drums? In the pantheon of drummers, who do you look up to?

Wertico: Oh everybody! That's why I bought so many recordings, be it rock, jazz or ethnic music. There are so many beautiful players out there and I've always wanted to hear as many of them as I could.

Chicago Jazz Magazine: Who are some of your favorite rock and jazz drummers?

Wertico: There are tons of them. Since I originally come out of the sixties, there are numerous great rock drummers that I love, like Keith Moon, Ginger Baker, Mitch Mitchell, John Bonham, Clive Bunker, Michael Giles, Robert Wyatt, B.J. Wilson, Thom Mooney and Paul Whaley, and others. There are just way too many to mention. And jazz-wise I go all the way back to the beginning. I'm really into the historical perspective of music, so I go all the way back to Baby Dodds and the earliest styles and recordings. I'd say that as far as jazz drummers, Roy Haynes was probably my main influence, as well as Elvin Jones and Art Blakey. There are also are a lot of great less-known drummers like Bob Morin, Eddie Marshall and J.C. Moses that played beautifully. Nowadays there are still a lot of wonderful drummers out there, but it's getting harder for people to have a distinct identity. The greater the number of players and the more notes that get played, then people have to look for the finer little details that make up someone's style. Whereas before, a drummer like Philly Joe Jones could just play a rim click on beat four-like on the song "Milestones"-and that would become one of his trademarks. [laughs] Nowadays, it's not quite as simple as that. Yes, a rim click on beat four was only one among many other things that marked Philly Joe's style, but that's usually always associated with him. Think how pure and simple that is!

Chicago Jazz Magazine: This is going to be an interesting answer coming from a fusion guy: How do you define jazz?

Wertico: Well, I really dislike the word fusion. It's misleading in its description because actually almost all music is fusion of sorts. And I really dislike the word jazz, too. I truly do, because ideally music should speak for itself. However, since sometimes music needs to be described in words or in print, then the review, preview, whatever, is in a different "language"-a language other than music-so people try to categorize things in order to attempt to describe them and make them understandable. Also to get back to the second part of your question, I really have no idea what jazz is anymore, I really don't. Originally jazz was called jass, J-A-S-S, but that was changed after mischievous kids would cross out the J, only leaving the word ass. But the word jazz wasn't actually coined by musicians and neither was the word bebop. Critics came up with those names. But, all descriptions aside, I like to think that a true jazz player is somebody different from someone that can sort of "play" jazz. I believe jazz can also be viewed as a type of lifestyle. It's a certain outlook on life. For instance, when I cook a meal, I'm always improvising. Now, you can be a good all around musician and sort of play many styles of music, including jazz, by referencing certain scales or playing certain beats, et cetera, but that doesn't necessarily make it jazz. It's like any language-if you know a few words in French that doesn't necessarily mean that you can speak French. So I think jazz is as much an attitude as anything else. So when you say fusion, for me, the term fusion can mean that a lot of different styles are combined to make a new type of sound. Actually, another thing is, that even though most music is a type of fusion, that doesn't necessarily mean that all fusion musicians are good at playing any or all of the original styles individually. But usually if a musician has a strong jazz background, that gives them certain improvisational skills that helps them play in a multitude of styles. It gives you a very solid musical foundation. In rock, you can improvise as well, but generally it might be over only a few chords or it might be over more of a static groove, whereas jazz can be anything from Dixieland to avant-garde and beyond. But to get back to your original question, there have been so many styles created over the years, and so much crossbreeding, god knows what the stuff is anymore.

Chicago Jazz Magazine: What has jazz brought to your life that wouldn't have been there had you not gotten involved with jazz?

Wertico: I really don't know. That's a great question and I love questions like that, but my answer, without trying to be cute, is that since I am what I am, I really don't know what else would have been out there had I chosen a different musical path. And since I'm happy with where I'm at, I guess jazz has given me a pretty good life. It's given me ways to express myself that are totally fulfilling and it's also allowed me to be heard on the international stage-because it's one thing to express yourself, but you could also just be talking to yourself in a closed dark room! [laughs] So it's given me an audience, it's given me an international forum to be able to express my views and have them heard, and it's allowed me to have a comfortable lifestyle. It's also allowed me to see the world countless times and to not be treated as a tourist, but as an honored guest. It's really given me so much and I'm truly thankful.

Chicago Jazz Magazine: Do you remember receiving any words of advice or compliments that gave you hope that what you were doing was on the right path?

Wertico: Well, I remember a few comments that people said to me over the years that have greatly affected me, luckily in a positive way, because the wrong words can really destroy artistic growth. When I was young and breaking in on the scene, I played a gig that had bassist Eddie Calhoun on it-he was Errol Garner's bass player for years. After the first set he said to me, "Kid, you'll always work!" and I said, "What? What do you mean?" and he said, "You'll always have work because you play happy drums! Your drumming puts out positive energy." That really stuck with me all these years. A couple of others are when bassist Ron Carter told the students at a bass convention in Evanston that I was house drummer for back in the eighties, "If you can't keep time with this drummer, then you can't keep time period!" Also, one time guitarist Ross Traut told me whenever he got lost in a tune, he could listen to me and know where he was. One of the best ones happened last year when I was playing with guitarist Larry Coryell. At the end of the night a guy from the audience came up to me and said, "The way you played those drums tonight, they're going to have a baby in nine months!" That one really killed me!

Chicago Jazz Magazine: Have you worked with many singers?

Wertico: Yes, and I love working with singers.

Chicago Jazz Magazine: What do you have to do differently as a drummer when you're working with vocalists as opposed to being in an instrumental setting?

Wertico: Well, it depends on the vocalist. But I know thousands of songs, and of those songs, I know almost all of the lyrics. I love lyrics-maybe that's one reason I like rock music, too, because I like words, images and stories. So when you work behind a singer, sometimes it's about being sensitive to dynamics, because you don't want to bury the singer with too much volume and power. Also, there's a certain phrasing issue, because time-wise, you don't want to step on someone that's trying to sing a phrase. With instrumentalists it's the same thing. If you're playing behind a horn player, you don't want to be stepping on the end of their phrases by crushing fills and by rushing the time. But especially with a singer, you want to give them room so they can actually tell their story. Musically you want to lift them up and give them all the support possible. But many of the really good singers are also good musicians as well, like Sarah Vaughan or Carmen McRae. If need be, they could tell the piano player to go home and they could sit at the piano and play the gig themselves. You know, I think most musicians actually wish they could sing. I wish I could sing, or at least sing well. [laughs] I can sing up to a point, but I can't control my voice well enough and my vocal range is too limited to get out what I want to get out. So I try to sing through the drums instead. It's almost the same, but the lyrics are harder to understand! [laughs]

Chicago Jazz Magazine: In a slightly different vein, you've done a lot of work with Ken Nordine.

Wertico: Yeah, but he's a whole different thing, too. Ken just lets you play whatever you want to play. With many of the tracks I've done with Ken in the studio, the words were written after we played the music. When you do his radio show he sometimes has you jam-just play free, and then he makes the story up around what the musicians played. But on gigs for instance, if he calls a tune like "The Akond Of Swat," or whatever story he has in mind, then usually he'll ask the band to create a mood or a groove and then we'll come up with something on the spot that hopefully will give the words a proper bed. It's a very liberating approach. But there again you want to stay out of the way, so that you don't detract from his voice and the story that's he's telling. He also has a different way of phrasing. His phrasing is not necessarily about swing-it's about telling the story. Also the timbre and resonance of his voice are so amazing that you want to let that shine through and you don't want to step on it. I love working with Ken. What can I say? He's truly a genius.

Chicago Jazz Magazine: Besides performing, you also do a lot of teaching.

Wertico: Yes, that's something I really love to do and I've been teaching drums for almost forty years. I've been on the Wind & Percussion faculty at Northwestern University for fifteen years and I've been on the jazz faculty of Chicago College of Performing Arts at Roosevelt University for five years. In fact, I'm currently the Interim Head of Jazz Studies at CCPA. It's wonderful to be able to transform a program into one that you yourself would like to attend. I really want to make our program one that truly specializes in teaching the art of improvisation. One of the new changes I've made there is to make the whole combo program "style specific." For instance, every semester, each combo focuses entirely on a different style and period of jazz-be it, early swing, bebop, post-bop, avant-garde, fusion, et cetera-so students learn what each style really demands and they become familiar with the compositions, artists and individual characteristics of each style.

Chicago Jazz Magazine: What other kind of projects have you not done that you were hoping to do?

Wertico: Not too many, actually. I've occasionally thought about whom I would want to play with, that I haven't played with yet. Obviously, I could probably name a variety of names of great musicians that I wish I'd had a chance to work with, but I don't feel like my life has a void in it at this point. I don't feel like since I didn't play with this or that artist, or wasn't in this band or that band, that I'm going to die without somehow fulfilling my dreams. I've been incredibly fortunate. It's been great-it's been a great career and hopefully it will keep going. I work out everyday, I practice everyday, the students that I have are wonderful and they inspire me, as well as, I hopefully inspire them. So it's still all systems go, even at the age of fifty-four. Sometimes I get mail now from AARP and I look at this mail thinking, Oh my god, how did that happen? [laughs] Because I still feel like I'm twenty!

Chicago Jazz Magazine: Tell us about the trio you currently work with.

Wertico: I love my group. It has John Moulder on guitar and Brian Peters on bass and miscellaneous instruments. I think we have a really unique sound and approach and I want to somehow get more people to hear it. But it's hard to lead a band because there are so many things you have to deal with outside of the actual music. At the present time, I don't have an agent or manager and the record labels I've been with have either been small or they've gone under. The record business-the music business in general-is really tough. Also, because our music really doesn't fit into a general mold, it makes it tougher to market us. But like they say, If it was easy, everyone could do it!

Chicago Jazz Magazine: Aren't you working with the British label, Naim?

Wertico: Yes, Naim is a fine label, but Naim is also an audiophile label, so it's hard to find our recordings a lot of times. Also, they're not the kind of label that's going to put a lot of money out there for you to go out on tour. Sometimes the recordings that you are really proud of only get marginally distributed to certain areas-it's hard. That's the thing I was talking about earlier about Pat. If you can get support from a major label and have some big guns behind you, then their machine is powerful and organized and they're going to have all their ducks lined up in a row. As soon as the recording is released, it's going to be in the stores and all the reviews will come out at the right time and the tour will be happening at the right time. When you're just trying to make music and put out CDs on CD Baby, or on a small independent label, you usually don't have that type of coordinated effort happening for you. And I don't really have time to do all of that myself. I'm too busy making music and teaching and I don't want to sit there all day, everyday, in front of a computer doing all that busy work-that's usually what you hire other people to do. So my trio usually only plays a couple gigs a year and a lot people don't even know about it. But hopefully that will eventually change...we'll see.

Chicago Jazz Magazine: Talk about your band members.

Wertico: John Moulder, the wonderful guitarist and composer, has been in my trio since its inception in 1994. We've been great friends for many years and I've played on all his recordings and he's played on many of mine. Eric Hochberg was also in the band on bass for a long time. Eric's an extraordinary musician, but because of that, he's also extremely busy most of the time. Eric is one of my best friends, but a lot times he had to get out of my gigs, sometimes at the last minute, to do his own leader gigs. So I started using a brilliant young musician, Brian Peters, who plays bass, violin, guitar and miscellaneous effects. He's also a brilliant recording engineer...he's just brilliant, period. He's brought a different slant to our music by using various MP3s that he's created, as well as utilizing other unusual sounds like the Theremin during our performances. Sometimes he sounds like four people on stage. So the band has a totally distinct sound. One of the greatest compliments we often receive is, Wow, you guys don't sound like anyone else! That's one of the great things that we have going for us.

Chicago Jazz Magazine: When you look back on your career is there anything in particular that documents Paul Wertico at the height of his creativity?

Wertico: I have no idea, because there are so many of sides of me and I don't put all of those sides out at any one time. There's the Pat Metheny Group side, which I'd like to think of as being very musical, but it was also about staying out of the way, almost like an orchestral percussionist. There's the Earwax Control side, especially on the CD, 2 LIVE, which is a great live recording with me playing not only drums, but also electronics and keyboards. I love that CD! But those concepts are very different. I've also done a number of things with Kurt Elling-the stuff with Ken Nordine, the recordings and concerts with SBB, which is a progressive and hard hitting blues rock band that's one the most famous Eastern European rock bands of all time. I've been playing with them for several years. There's my playing with Larry Coryell, who is really a very musically generous leader-he gives me carte blanche to play whatever I want. However, there's no one recording that actually captures everything, which is good. Each one has a piece of who I am on it.

Chicago Jazz Magazine: Do you think a great drumming performance is based on what you're doing as a virtuoso or is it based on how you are interacting with the other players you are with?

Wertico: It totally depends on what the musical goal is. If it's a virtuosic solo, where all cylinders are firing, that's one scenario. But I always like discovering something new, so I never try to play the same thing twice. When people ask me how I come with new things and fresh ideas, I often tell them, Well, I always come up with new things because I don't know what I am doing! Now I don't mean that I'm ignorant or unaware of what I do. It just means that I try not to repeat what I've done and I try to explore new territory. You should always try to find something fresh. It's like in life-if you take who you are and then always impose yourself and your old views into each new situation, it gets boring. But if you're open to new situations around you, then everything is also constantly changing you as you're doing it. That's how I try to live my life and that's how I try to stay musically fresh-so the circumstances are affecting me as much as I'm affecting the circumstances. Musically, it's the same way with a band. If I only played preconceived stuff-which I would never do-it would be boring. I'm constantly listening to what other people are playing and then that gives me fresh ideas. I believe that if you try to live your life like that, everything becomes a lot more fun because everything is always new. Even something that seems totally simple-like "the million dollar beat" for example, which is basically just Boom-Bap-Boom-Bap-beats one and three on the bass drum, beats two and four on the snare drum, and eighth notes on the hi-hat. All by itself, it seems totally basic and almost boring. But try executing it perfectly for several minutes. You know, that's a feat in itself. Then, even if you played that same beat for a number of songs, that beat would take on a different meaning because there are going to be different bass lines, different chords, different lyrics, even different tempos. That beat then takes on a whole new characteristic with each new song. So how can you get bored playing that beat if everything around you is changing? Actually, how can you be bored, period?

Visit Paul’s website at: www.paulwertico.com

You are here: Home > Interviews > Chicago Jazz Magazine - January/February 2008